#17 When Those Around You Talk About Culture, What Do They Mean?

Explore an easier way to minimise misunderstandings, and encourage group members be on the same page regarding the culture they're helping to create.

A note to listeners and readers of Helpful Questions Change Lives:

In my first series of posts, I wrote about being aware of how our mental states can hijack us, in any moment. I pointed to how we can become more aware of the sensations, thoughts and feelings that sit behind these. And how witnessing them, from a detached, metaphorical distance, helps us be with each, returns us to a mental state of equilibrium - or what I described as one way of recognising wellbeing, - and respond accordingly, thus reducing the hijack’s negative impact.

I also suggested that if this looks true to you, changes in your own inner mental life, as well as that of others close to you, become a real, not remote, possibility. Together, you see you have more agency than might first appear over the events, people and circumstances that come your way. Conversely, of course, that agency may sometimes seem elusive when a hijack is in full swing.

In this second series of posts, signalled by the yellow background in the picture below, I explore what makes sense to you in your relationship with the different groups you’re a part of - teams at work, professional networks, family and friends, for instance.

I invite you to wonder what you and other members of these groups might see anew, were you NOT bound by sense making that may once have worked well for you, but may not any longer, in all circumstances.

Enjoy playing with the if-not-this-then-what question on the issues in this series. Let me know in the comments if they help or not.

Though I didn’t know it at the time, I once worked in a culture I now see was toxic.

It was headed by someone we privately referred to as “The Tyrant.” He led a financially successful organisation. In his eyes, therefore, he was succeeding. Delivering on what he was paid to do.

My colleagues, however, feared for their livelihoods. They knew speaking up was a risky business and often career limiting. They were judged solely by their monthly numbers. If they did well The Tyrant would laud them, if not, he’d publicly lambast them. Get your numbers wrong two consecutives months in a row and you were out.

No wonder then, being an accountant at the time, partly responsible for producing the monthly numbers, I had colleagues from across the business trying as many ingenious ways as they could think of, to game the system. Requests to delay payables to the next month, bring revenues forward, challenge the assumptions behind month-end accruals all featured. I couldn’t agree to them, of course, but I could empathise with those making them. They had families, mortgages, and reputations to protect, and feared their numbers might harm all three.

Motivation by fear is what seemed to drive The Tyrant. He once said this to a department head, “Fifty percent of what I say is brilliant, the other fifty percent isn’t. Your problem is you can’t work out which is which.”

My colleagues weren’t motivated though, they were in survival mode. Fearful more often that hopeful. And certainly not inclined to go the extra mile and be innovative.

Worse, we thought this was the norm for businesses. This is what the money-making machine did to us. The only option we had was to put up or shut up.

I upped sticks and changed career course. I concluded there had to be a better way to run organisations and transitioned from the world of finance to leadership development. That was in the mid 80s. I’ve been a lifelong student of what helps to bring out the best in people ever since.

Seeing the culture you’re in

As I took the culture I found myself in for granted, thinking “Well, that’s just the way things are”, I notice others do too.

Typically, people only talk about culture when there’s a recurring problem, pending doom, or they’re in disaster-recovery mode. Independent investigations into failures of projects and corporates often conclude the leadership either presided over, or built a culture of fear, blame, indifference, toxicity and so on. Yet executives and senior managers look genuinely shocked and perplexed by these findings; they find them hard to believe.

The analogies of a fish doesn’t know it’s wet and a fish rots from the head help explain this phenomenon. The former suggests when we’re deeply immersed in a culture, like the water a fish swims in, we’re unaware of it. Ask the fish "What's the water like?" and their response would be "What's water?" If a leadership, among other key influencers, are the biggest shapers of culture, and constitute the head of a fish in the the latter analogy, their very same lack of awareness can be fatal.

Both analogies are supported by this quote from Professor Ed Schein who’s work on culture has helped my own immensely. He said this.

“The only thing of real importance that leaders do is to create and manage a culture.

If you do not manage culture, it manages you, and you may not be aware of the extent to which this is happening.”

If noticing the culture you’re in can be tricky, yet it’s vital to do so if you want your organisation, department, team, family etc., to thrive, I suggest a useful starting point is to explore what the word culture could mean to you, and those around you. Being clear on this gives you a good base to build from.

A way of defining culture

The meaning of words depends on the context in which we use them. Culture seen from a societal standpoint, for instance, often refers to art, literature, music, architecture, core beliefs and customs relating to a period of time in different places around the world. For our purpose, though, I'm referring to the culture of groups in general and particularly in organisational settings.

In that context, I note that culture means different things to people. Some see it as too complex an idea, relating only to industrial sectors, large corporates, government departments, charities etc. “Culture is above my pay grade”, they argue.

While understandable, given the way we normally talk about organisational cultures, I think this is mistaken. Mainly because I’ve seen wildly different cultures between departments in the same organisation - Finance, HR, Operations and Marketing, say. Also, among different teams within the same department, and in different projects, either within a single organisation or made up of several different ones.

It seems to me cultures exist whenever groups of people need to organise to get stuff done - be they small groups or large. Our membership of them means we're helping to shape their culture.

As for defining what a culture is, I’ve seen leaders fall out over the role culture plays in enabling higher levels of performance. Some believing it’s a nice to have; something to turn their attention to when there’s more time. Others taking a leaf out of Ed Schein’s book, believing it’s integral to great performance, on the simple grounds that none of us can do well when we’re caught up in some unhelpful thinking that’s making us feel lousy. More on these differences later.

The definition I use to help clients figure out what they mean when they’re talking about culture is this one…

How people feel overall about the way things get done around here.

Or as Bill Marklein, Founder of Employ Humanity, puts it…

To me, defining culture this way makes sense because it’s easy to help others put it to the test.

For instance, how we feel about our role will show up each morning when we think about the working day ahead, as well as on a Sunday night. On average, that feeling may lift your spirits. It may also leave you feeling work is a necessary chore - like a burden you must endure to pay your way in the world. Anywhere between these extremes is possible too.

That feeling could be unique to you, of course. However, it’s likely colleagues will feel similarly, even if talking about it isn’t your custom and practice, as is often the case. (Remember how I and my colleagues thought our culture was the norm, so just put up with it, despite the fact it didn’t bring out the best in us?)

The underlying feeling is hard to hide too. We leak it out through our vocabulary, facial expressions and overall demeanour. Next time you walk into a meeting room where others are at work, or enter a building you’ve not been in before see if you pick up on it. How people working there feel about what they’re doing has a vibe to it.

Finally, by putting how people feel centre stage in the definition, we move away from the idea that we are all rational creatures only. We don’t only behave according to that rational part of the mind - the left hemisphere - we bring the emotional, right hemisphere and our physical sensations into play too. As we explored in Series 1, it’s the combination of these, after all, that drive our experience and what we subsequently do.

Let’s break the definition down a bit more.

How people feel overall

People refers to any configuration - a single team, a cross-functional project team, one or more departments, key accounts, one or several members of a supply chain, a location like a call centre, factory, head office, and so on.

The word overall relates to that general feeling you're left with once inevitable fluctuations around good days and bad days are ironed out. It’s gauging a trend rather than one specific event or incident.

The way things get done around here

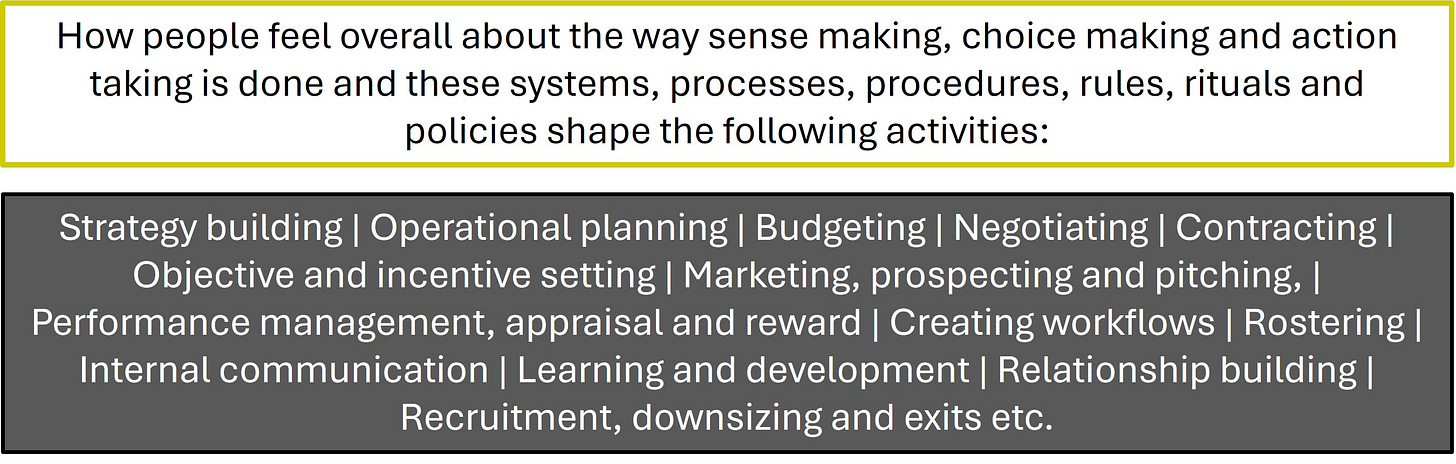

Things refer to the myriad of activities that take place regularly in a workplace. The box below lists many of them.

Around here locates these activities to a particular context in which the ways things get done take place. In frequent and familiar settings - the weekly team meeting, say, - and when on unfamiliar ground like launching something brand new, for example.

Back to the differences over culture that cause misunderstanding

I mentioned above how some see culture as a nice-to-have, while others see it as integral to how everything gets done. Another difference concerns the way managers think about the activities in the box above.

You’re not alone if you think culture is purely a behavioural issue that can be altered by applying a collection of tools on an as-needed basis to deliver a desirable culture.

The logic goes like this: if culture is purely about behaviour, all we do is tweak the tools at our disposal to deliver the change we need. For example, want more satisfied clients? Simply introduce tools such as new financial incentives, tighter performance objectives and manage these until the right result pops out at the other end.

Such a train of thought about what causes behavioural change is understandable. For some time, we’ve collectively thought about organising in mechanistic and machine-like terms. The machine metaphor seeps into our routine thinking and finds expression in some leaders’ vocabulary. They’ll speak of “inputs,” “outputs,” “throughputs,” “resources,” “standards,” “tools,” “levers” etc.

To be clear, having tools that help us organise, matters. They provide direction, set standards, lay out what’s expected and make managing activities easier.

A pitfall, however, is they are not in and of themselves the only determinants of behaviour. The way people feel about them matters too.

When people’s wellbeing is good more often than not, the culture in your team, department, organisation - or whatever your unit of analysis happens to be - is working in your favour. Sure, challenges crop up from time to time, but people aren't fazed by them. They enjoy puzzling out solutions and working closely with each other to do so, even when they disagree at first.

Conversely, when under pressure, and illbeing has the ascendancy over wellbeing, individuals may forget or ignore particular tools - like rules, incentives, controls etc., and start gaming the system, much like my colleagues who were worried about their livelihoods did. This doesn’t make them mad, bad or sad, they’re just doing what makes sense to them to survive.

When tools and mechanisms leave people feeling frustrated, overwhelmed, and undermined even, the behavioural-change logic described above causes a lot of head scratching.

Despite efforts to prevent problems, they mount and making headway is slow or non-existent. To boot, in the absence of an alternative, managers unwittingly compound them. Understandably, they double down by using more “tried and trusted” tools to deliver better solutions. More rules, tighter controls, stretch objectives, new contract clauses etc.

And they may get lucky and hit on a temporary fix. But, unless the underlying culture - how people feel overall about the way things are done around here - changes too, the fix is unlikely to last. Consequently, persistent problems - seen in how teams converse and relate with each other...well…not only persist but intensify too.

In my experience of developing teams, rather than double down on the tools that produce same-old, same-old solutions, we need a new way to break through what can feel like ingrained, knotty and seemingly intractable challenges.

Having an awareness of culture, unlike those fish, helps! So does a clear definition that saves much confusion. Ditto being mindful of this pitfall: logic alone doesn't drive behaviour, feelings are equally important.

In the next post I’ll delve a bit deeper into how people feel about the way things get done in the groups that matter to you, and how you might help them change the culture themselves should that be needed.

Until then,

Kindest,

Roger

Be In Conversation With Me

I set up HQCL to help those who feel stuck in all or bits of their life.

The content here may quench your thirst for what helps you change your inner life and have a better experience of your outer one.

You, however, may want to go further, to satisfy two needs.

First, to explore unanswered questions that sometimes remain, even after letting what you’ve learnt here sink in.

If you’re in this situation join me for a 45-minute, online Ask Me Anything Conversation using this link.

Though this is a paid-for service ordinarily, I still don’t want money to stand in the way of you feeling helped. If the cost is unaffordable, therefore, just drop me a note explaining what you’ve learnt so far, as well as what questions you want answers to, and I’ll send you a link to join the AMA Conversation for free.

Second, to have me alongside you for a while, guiding you as your awareness of the contents of your consciousness grows, and you observe changes in your experience of life.

If you feel you’d benefit from working one-to-one, in a more personalised way online, my 2-hour Guiding Conversations will help.

Guiding Conversations put you in charge of how many you need for two reasons.

First, we all learn at different rates. Realising the life-changing potential behind understanding the why-do-you-experience-life-as-you-do question, and feeling it profoundly, can take a short amount of time for some, longer for others. These conversations enable us to by guided by what emerges in them and respond to what you need at different points in time. They mean we don’t have to force-fit stuff into a pre-set number of slots over a fixed time frame.

Second, knowing what each one costs, you can tailor the size of the investment you want to make in changing your life, according to your means.

Other useful, free posts.

You can find all the posts in my first series here.

While it’s good to pick those whose titles speak to you most, I recommend these five in particular:

#3 Being Right Here Right Now - Hard To Do? - This covers the idea of being fully present and what distracts us from that.

#4 How We Experience Life Is Mysterious. Isn’t It? - This goes to the heart of the mystery surrounding why we get sensations, thoughts and feelings in the first place, and what the implications are of being at ease with this.

#5 What Influence Do You Have Over Your Experience In Each Moment? - Here I look at what is and is not within our control and where we can exert influence when changing our experience.

#6 If You Saw Wellbeing Like This, What Difference Would It Make? - If BEING WELL RIGHT NOW is the goal, this describes what that’s like and how our feelings can be a useful warning sign of wellbeing’s absence.

#8 Why Do You Respond To “Difficult” Others Like That? - Here I invite you to consider some of the deeper, often-hidden assumptions we hold about the nature of human nature and their impact on your experience of difficult others.

In that context, I note that culture means different things to people. Some see it as too complex an idea, relating only to industrial sectors, large corporates, government departments, charities etc. “Culture is above my pay grade”, they argue. (to quote your own wonderful self).

Leaders create expectations, safety, dysfunction, truth, lies . . . and, as dangerous as it is to suggest a root cause, they create (and support) context, the surrounding tissue of nutrition that feeds growth or impedes it.

Thanks for your addition to my content of understanding.

I believe 'twas myself indeed.