#23 How Valuable Are Shared Values?

Explore the extent to which shared values change key influencers' mindsets.

A note to listeners and readers of Helpful Questions Change Lives:

In this second series of posts, signalled by the yellow background in the picture below, I explore what makes sense to you and those around you in the different groups you’re a part of.

The invitation is to wonder about what you and other members of these groups might see anew, were you NOT bound by sense making that may have served you well at one time, but doesn’t so much now.

I help you do that by sharing stories of how my own trains of thought have changed direction on various group-related topics. Not to convince you of anything, or that I’m right, more to share what makes sense to me now but didn’t before. My intention is to provoke curiosity about whether my own path could be of help to you in your context too.

Enjoy playing with the questions in this series. Let me know in the comments if what you discover helps or not.

In the 90s I did much pro-bono work for a charity called Tomorrow’s Company (or TC for short) here in the UK.

TC emerged out of inquiry set up by The Royal Society of Arts, Commerce and Manufactures ( The RSA), which had been inspired by a question posed by the Irish author and philosopher specialising in organisational behaviour and management, Charles Handy. His question was simply this..

What is a company for?

At the time, the idea that the primary responsibility of directors was to maximise shareholder wealth, advocated by the economist Milton Friedman among others, was in the ascendancy. It had got traction under Margaret Thatcher’s government and inspired many government reforms aimed at reducing the role of the state in the provision of energy and services. The captains of British industry that made up the RSA’s inquiry team, felt a counter narrative was needed; one that recognised a company should be for creating value on behalf of multiple stakeholders, shareholders included.

TC’s ‘five plus one’ model encapsulated the essence of the Inquiry’s findings. It suggested that if a company is to thrive in the longer term (i.e. tomorrow and beyond) it needed a metaphorical licence to operate. That would only be available if it created value for five stakeholder groups - customers, employees, suppliers, shareholders, and wider society.

The one referred to the company’s leadership. It suggested they needed to have clarity of purpose and a shared set of values. The latter governing how they conducted relationships among themselves and all five stakeholder groups.

Critics would argue ‘five plus one’ was too woolly or soft. It stopped the C Suite focusing on the one core thing that mattered - the bottom line. We would counter this critique by citing an extensive study done by Jim Collins and Jerry Porras in the US, the results of which they shared in their book Built To Last: Successful Habits Of Visionary Companies.

The study compared the market leader in a given sector - as measured by share price appreciation and dividends returned to investors over a 50+ year time frame - with their nearest rival. Its focus was what contributes to this often significant gap between the market leader and the firm in second place. For instance, American Express led Wells Fargo, Hewlett Packard beat Texas Instruments, IBM outperformed Burroughs, Disney beat Columbia, Boeing trumped McDonnell Douglas etc.

It concluded that what primarily made the biggest difference was that leaders could simultaneously ‘preserve the core and stimulate progress’ while their followers had just one focus - the financial bottom line.

(As an aside I watched Downfall The Case Against Boeing on Netflix last night. It showcased how the merger between Boeing and McDonnell Douglas altered Boeing’s one-team-focused-on-quality culture significantly. The new leadership wanted to impress Wall St. They prioritised cutting costs as well as corners. The Boeing name that had once symbolised the gold standard for the aviation industry, was subsequently held responsible for two of their 737 Max aircraft falling out of the sky, killing 346 people. Devastating. I have more on failures like these later.)

Back to TC though, c. 1997. Great inquiry by the RSA that included serious players from corporate Britain. A nice and simple model, supported by a strong research base, meant any company now had what they needed to succeed today and tomorrow.

Or so I thought.

A wake up call

Around that time I and a colleague were supporting the growth of a wind turbine blade manufacturing factory in the renewable energy sector. They were growing from 50 employees to over 500 and were tasked to bring production times down from 3.5 days to 20 hours or less.

Our work was to help the leadership embed a culture of learning. As the number of managers grew we facilitated an increasing number of learning groups for them. Every 6 weeks or so, six managers would bring a challenge they were stuck on to the group and together they’d explore potential new ways forward.

Participants loved these groups. They provided time to think they wouldn’t have otherwise had. They built friendships among colleagues from across the business. Hearing what other managers were trying to resolve fostered a compassion for each other. Participants would often say they got more from helping others than they did from being helped themselves.

Though many had been sceptical about the value of these groups to begin with, that waned after just one or two sessions. The camaraderie these guys (they were mainly men) created was remarkable. It extended to loyalty to the factory’s leadership too.

Armed with the knowledge I’d built up supporting TC, it occurred to me it was time to broach the question of developing a set of shared values with the factory’s leadership. If they took a leaf out of the Built to Last book, and got fired up about the 5+1 model, their continued growth would be pretty much guaranteed I thought.

Imagine my shock therefore when the Chief Engineer on the leadership team, let’s call him Ron, said words to this effect after listening to my case for a shared purpose and values workshop.

“I understand the importance of scientific research. Lord knows in my world of the physics of capturing energy from the wind, it’s pretty vital. Social sciences on the other hand, like how people behave in organisations, is a different kettle of fish.

“The idea of generating and preserving our core purpose and values while simultaneously stimulating progress resonates. I’d say we’re pretty clear about our purpose though - to make high-quality blades, efficiently, so that the world weens itself of fossil fuels for its energy quicker.

Why, though, do we need shared values?

“Think about it, even if we could agree what they are from the hundreds that exist, and put them on the reception and factory walls, wouldn’t that somehow destroy the essence of what we’re building here? Once you name what people feel is important it takes on a completely different form.

“The maths are problematic too. Suppose we narrowed it down to say 6 values, which could take quite a while by the way, and there are 500 of us, what’s the probability that all of us share them? Or would remember all six in every situation? Extremely low I suggest. If you were to then ask what’s the probability we actually use them in practice, even if we did remember them, that probability falls very close to zero.

“Sorry to knock your suggestion down Roger, but I don’t want a set of values to become a weight around our neck. Nor act like some sacred set of rules everyone must abide by, whether they’re feeling it or not.

“What matters is this - we are as aware as we can be of how we’re making sense of each situation we encounter, and continuously learn about what does and doesn’t help us each time. That’s the brilliant thing you’re helping us with in the learning groups, and what is ‘stimulating progress’ as the Built To Last book puts it.

“In my view that’s all we need. We don’t need to copy and paste what others have done, or what social science academics claim to have worked given their model of successful habits aligned to financial outperformance. We can plough our own furrow.”

My ego was dented somewhat at hearing this, I’m not going to lie. I felt deflated too.

But I, like many others in the factory, respected Ron a lot. He was the ultimate key influencer. People looked up to him. He was loyal to them. Passionate too - he believed engineers could save the world and he was keen to play his part in the renewables sector. He helped people at the factory, me included, feel like we working on something important. Something bigger than any one of us. Whatever label you use to describe that something, it was contagious and felt good.

As the years have rolled by, that exchange with Ron kept whirring away in the recesses of my mind. Though he was responding intuitively to my proposal, what he said resonated deeply with me.

Further reflection, new assignments with other clients, and more reading, particularly the literature surrounding corporate failure, and

‘s excellent Substack - - have led me to this conclusion when designing development programmes for key influencers…..organisations don’t have values, individuals do. Organisations have cultures.

McKinsey & Co, a leading consulting firm, invented the shared values concept as part of its 7S model. Yet recently, by September 2023, it had been fined $870m for helping “turbocharge” (their word) opioid sales in the US amid a crisis that contributed to more than 450,000 deaths. If you look at their website it clearly states that one of their values is ‘Adhere to the highest professional standards.’

Carillion was a large main contractor primarily in the UK construction industry. It’s corporate values included integrity, collaboration, excellence, and sustainability. However, when the company failed to secure a bail out from the UK Government just months after reporting good profits and dividend pay outs, it faced significant criticism and scrutiny for financial mismanagement and corporate governance failures. Soon after it collapsed.

The corporate values on the websites of other failed organisations below, make me think they were anything but shared by all those that worked there. How could they have been? Had it not been for some courageous whistle blowers many of these scandals may have never seen the light of day.

The Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust and Winterbourne View Trust - both patient safety and unnecessary-death scandals.

The News of the World and The Daily Mirror - phone hacking.

The Metropolitan Police - law breaking by officers alongside institutional racism, misogyny and homophobia.

UK banks - the LIBOR interest rate fixing scandal.

And what has become apparent to the whole nation more recently..

The Post Office - wrongly prosecuting sub postmasters because of a computer system fault.

I suggest the values of key influencers within these organisations contributed to their downfall. I can’t know for sure, of course, I can’t read the mind of these individuals, but it would seem likely that values such as those below may have driven the way sense-making, choice making and action taking got done in these organisations:

Greed: Prioritising personal gain, wealth, or power above ethical considerations, social responsibility, or the wellbeing of others.

Exclusivity: Promoting elitism based on factors such as wealth, social status, or identity, which can foster discrimination, prejudice, and marginalisation of certain groups.

Authoritarianism: Valuing control, dominance, and obedience to authority at the expense of individual freedoms, autonomy, and democratic principles.

Hubris: Excessive pride, arrogance, or overconfidence in one's abilities or accomplishments, leading to a disregard for advice, criticism, or consequences. Hubris can result in reckless decision-making, failure to learn from mistakes, and a lack of humility or empathy towards others.

Key influencers’ values coalesce into a mindset or an automatic way of making sense of the world around them and behaving accordingly. A mindset underpins the culture in their sphere of influence - ‘the way things get done around here’. Unless their automatic sense making changes first, nothing much else will, I’ve come to realise.

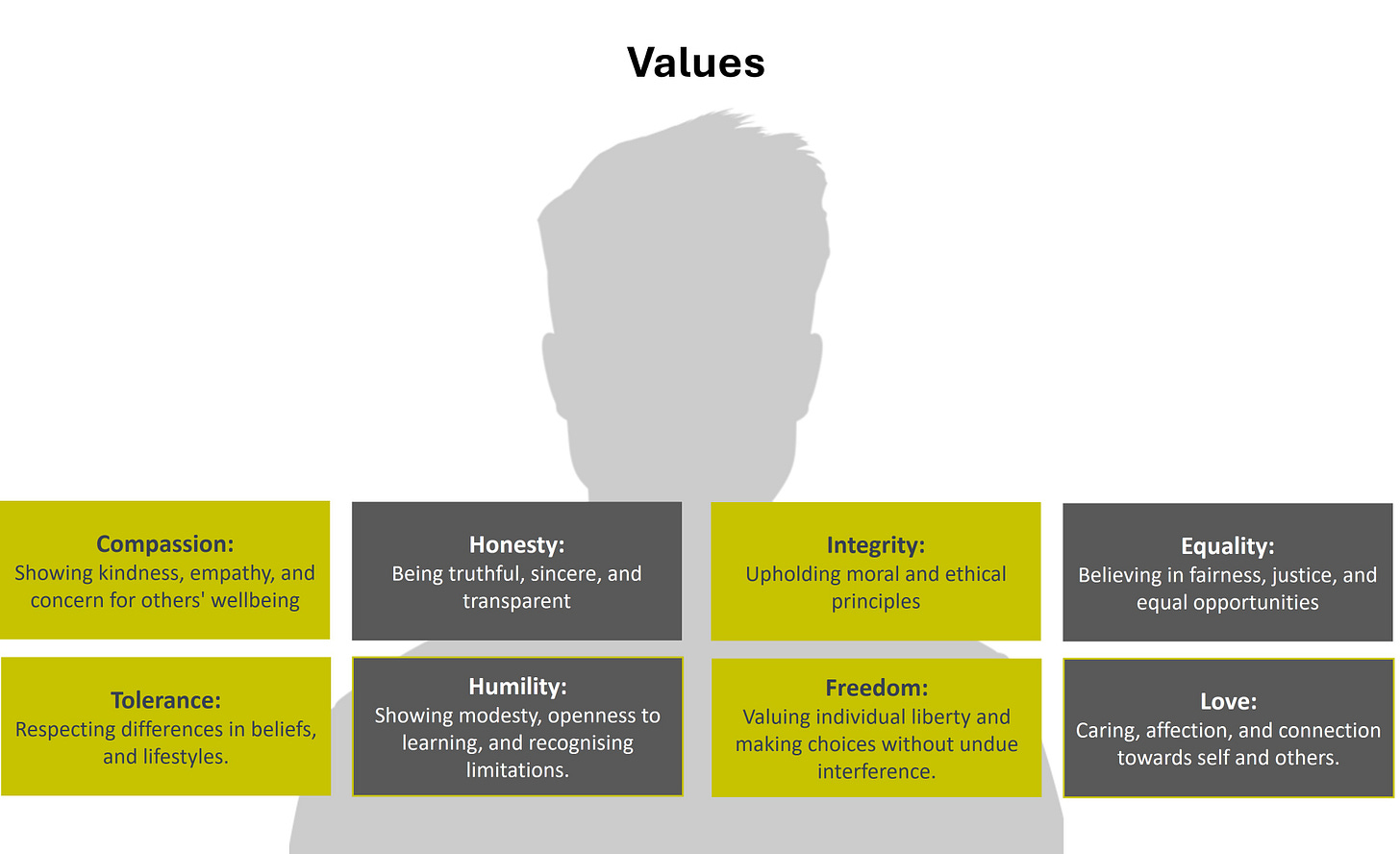

Now, I know some will say not all key influencers have harmful values like those described above. Furthermore, successful organisations have been built on values people believe in and, yes, share. Values such as….

If that’s the case for you, fantastic. If it’s working and people feel good overall about the way things get done in these workplaces, that’s just great. And what’s needed.

And, take heed of Ron’s caution based on maths - these values may not be as shared as people think in every situation. Additionally, for me, I’m now mindful of the fact that when there’s a need to intervene, to develop a new mindset and culture, the chances are something is awry. Or there’s an opportunity to be even better. Or there’s a seemingly intractable problem a group can’t resolve: despite previous attempts, it has not dissipated and is affecting performance.

In other words we don’t intervene typically when things are going well and group members can ingeniously find effective ways through even very challenging circumstances. They just get on with being at their brilliant best.

When this is not the case though, my starting point isn’t any longer to run a programme designed to produce a set of shared values. I’ve found what helps more is to zoom in on 1) just one core value - wellbeing - and 2) key influencers’ sense-making.

Sense making, be it shaped by potentially harmful values as above - greed, elitism, control over others, being over confident etc., our conditioning, past experiences and more - can innocently inhibit wellbeing. Seeing it in action though, in real time, and being as open as we can about it, helps reduce this risk considerably. As your, mine and key influencers’ minds settle and restore wellbeing, we notice new insights arise that help us thrive no matter what challenges and uncertainties we face.

Next time I’ll explore sense making in a bit more depth.

Until then,

Kindest,

Roger

Be In Conversation With Me

I set up HQCL to help those who feel stuck in all or bits of their life.

The content here may quench your thirst for what helps you change your inner life and have a better experience of your outer one.

You, however, may want to go further, to satisfy two needs.

First, to explore unanswered questions that sometimes remain, even after letting what you’ve learnt here sink in.

If you’re in this situation join me for a 45-minute, online Ask Me Anything Conversation using this link.

Though this is a paid-for service ordinarily, I still don’t want money to stand in the way of you feeling helped. If the cost is unaffordable, therefore, just drop me a note explaining what you’ve learnt so far, as well as what questions you want answers to, and I’ll send you a link to join the AMA Conversation for free.

Second, to have me alongside you for a while, guiding you as your awareness of the contents of your consciousness grows, and you observe changes in your experience of life.

If you feel you’d benefit from working one-to-one, in a more personalised way online, my 2-hour Guiding Conversations will help.

Guiding Conversations put you in charge of how many you need for two reasons.

First, we all learn at different rates. Realising the life-changing potential behind understanding the why-do-you-experience-life-as-you-do question, and feeling it profoundly, can take a short amount of time for some, and longer for others. These conversations enable us to by guided by what emerges in them, and respond to what you need at different points in time. They mean we don’t have to force-fit stuff into a pre-set number of slots over a fixed time frame.

Second, knowing what each one costs, you can tailor the size of the investment you want to make in changing your life, according to your means.

Other useful, free posts.

You can find all the posts in my first series here.

While it’s good to pick those whose titles speak to you most, I recommend these five in particular:

#3 Being Right Here Right Now - Hard To Do? - This covers the idea of being fully present and what distracts us from that.

#4 How We Experience Life Is Mysterious. Isn’t It? - This goes to the heart of the mystery surrounding why we get sensations, thoughts and feelings in the first place, and what the implications are of being at ease with this.

#5 What Influence Do You Have Over Your Experience In Each Moment? - Here I look at what is and is not within our control and where we can exert influence when changing our experience.

#6 If You Saw Wellbeing Like This, What Difference Would It Make? - If BEING WELL RIGHT NOW is the goal, this describes what that’s like and how our feelings can be a useful warning sign of wellbeing’s absence.

#8 Why Do You Respond To “Difficult” Others Like That? - Here I invite you to consider some of the deeper, often-hidden assumptions we hold about the nature of human nature and their impact on your experience of difficult others.

Thanks, Roger. Lots of stuff.

I especially appreciate the differentiation between culture and values.

X)X)